Peeping Tom

Directed by Michael Powell

Running time: 1hr41 | REVIEWED BY GUY LODGE

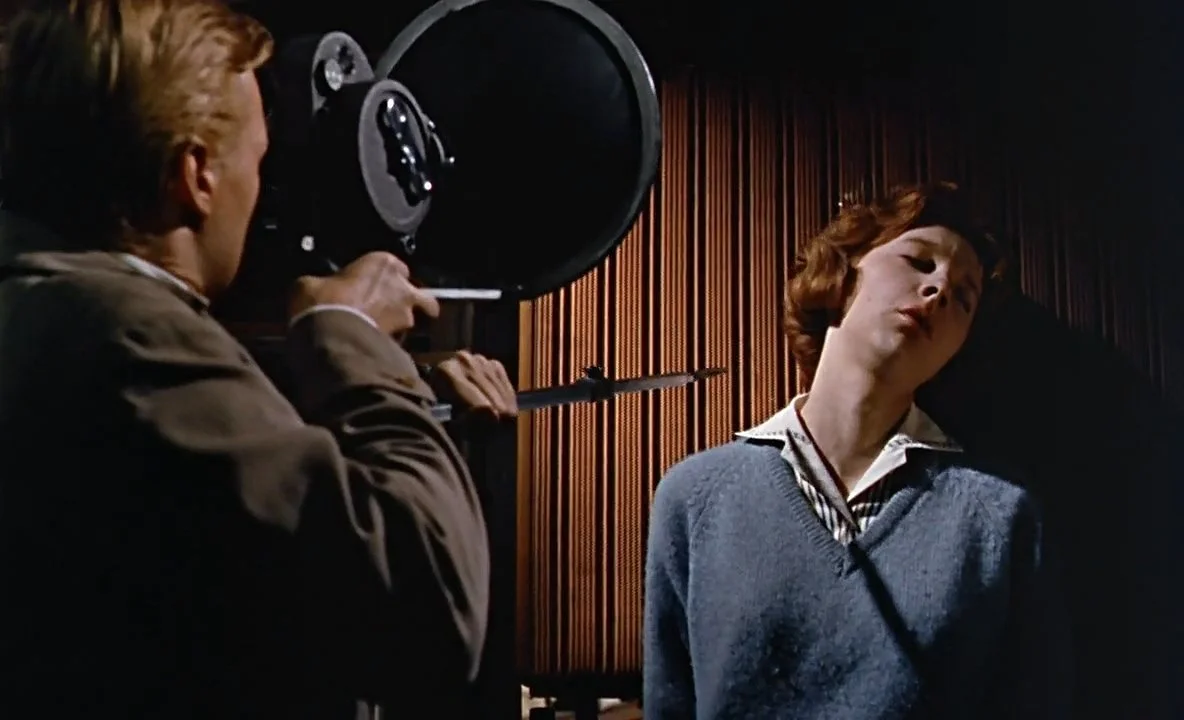

Carl Boehm and Anna Massey in Peeping Tom

Last week’s Film of the Week legend, Martin Scorsese, once stated that the entire art of film directing could be articulated via two contrasting films: Federico Fellini’s 8½, he said, “captures the glamour and enjoyment of filmmaking,” but Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom “shows the aggression of it, how the camera violates.” The dual impulse to entertain and to attack lies in every filmmaker: Certainly Powell, aged 55 when he made this tart, multi-bladed, still-startling psychological thriller, had already amply proven his facility with cinematic glamour and enjoyment in such jewel-toned beauties as Black Narcissus and (as we celebrated recently) The Red Shoes. Freed from his long-term collaboration with Emeric Pressburger, Powell wanted to try different things. Here was nothing if not a different thing.

You can see why the icy nastiness of Peeping Tom, an unblinking metatextual probe into the weaponisation of looking, so shocked and repelled unprepared audiences in 1960, leading to its relative commercial failure. The short-sighted critics at the time — who largely wrote off Powell’s adventurous consideration of exploitation, in matters of cinema and sex, as an exercise in sadistic leering — are less easily excused. Clearly Powell sees something of himself, and all filmmakers, in his warped protagonist Mark Lewis (played with unnerving poise by Austrian actor Carl Boehm), a young London film crew worker who indulges his auteurist ambitions by covertly filming and following women, keeping the camera rolling as he murders them, and watching the footage at home afterwards.

But it goes without saying that this is an unforgiving self-identification on the director’s part, querying just how much power he wields with the camera lens, and how much damage it can do. Who is the greater voyeur — he who makes violatory images or he who consumes them? (In 1960, at least, that was very much the intended pronoun.) By collapsing these vantage points into one character, Powell and screenwriter Leo Mark coolly comment on the complicity between filmmaker and audience. It’s notable that Peeping Tom was made in the same year as Psycho, another defining work by a veteran filmmaker carving out explicit, uncomfortably real new territory in the horror genre, with both films centred on marginalised young men who can only find violent expression for their desires.

Peeping Tom trades in matters of trauma, toxic masculinity and incel dysfunction that are de rigueur in horror today, which isn’t to say it feels dated or passé. You freeze and hold your breath with the film as it pulls back the curtain on realities nobody really wanted to admit or address in the cinema on a Saturday night; you fear not just for the women on screen, but for your fellow viewers, then and now. Perhaps we’re more ready for Powell’s exquisite provocation today than people were 63 years ago. But what does that say about us?

PEEPING TOM (1960) Written by Leo Marks | Shot by Otto Heller | Edited by Noreen Ackland